Yuri's hidden gravel gems: Patagonia's mine and wine country

"There are very few places that I’ve experienced by bike where I’ve felt so insignificant, dwarfed by the expanse of the landscape, in awe of its stark beauty, and grounded by the sounds and the silence."

- (opens in new tab)

- (opens in new tab)

- (opens in new tab)

- Sign up to our newsletter Newsletter

There are gravel riding gems everywhere, but they can be hard to find. This is the second installment in a series that aims to help you get inspired and find your next best gravel adventure.

In this article, off-road pro and gravel veteran Yuri Hauswald puts the spotlight on Patagonia, Arizona and its mining roots.

First installment: Tuscany vibes in California's North County

Before general Pancho Villa charged through this vast desert expanse searching for cattle he could steal from the local ranchers, it was home to the Sobaipuri, Papago, and Apache people. The San Rafael Valley, just 60 miles south of Tucson, is part of Arizona’s unique Sky Island ranges, and lies at the intersection of the Rocky Mountains, the Sierra Madre, the Sonoran Desert, the Chihuahuan Desert, the Great Plains and the Neo Tropics. This unique expanse of land that borders Mexico is home to many different bird, bee and butterfly species, boasts the greatest mammal diversity in North America, and is home to a unique mixture of wild west rancher, artist, miner, birder and outdoor enthusiast population. And you know what else it has? Hundreds of miles of empty, high desert gravel roads, just waiting to be explored on two wheels.

It had been the lure of ore, silver and lead that drew eager prospectors to this dynamic region of Southeastern Arizona in the late 1800’s. The only problem was that it wasn’t theirs to take, and the Apache, as well as other tribes, made it quite difficult [rightfully so], and bloody, for them to put down roots. Patagonia was eventually settled by the late 1800's as a supply and railroad hub for the mines in the nearby mountains and lead to the creation of other small mining towns like Duquesne, Harshaw, Washington Camp, and Mowry that dotted the flanks of Red Mountain and the outlying areas towards the San Rafael Valley and the Mexican border farther to the south.

I discovered this hidden gravel gem eight years ago when I attended a first of its kind gravel camp curated by Heidi and Zander Ault, the founders of The Cyclist’s Menu, a company that provides unique cycling and food experiences to curious and adventurous athletes.

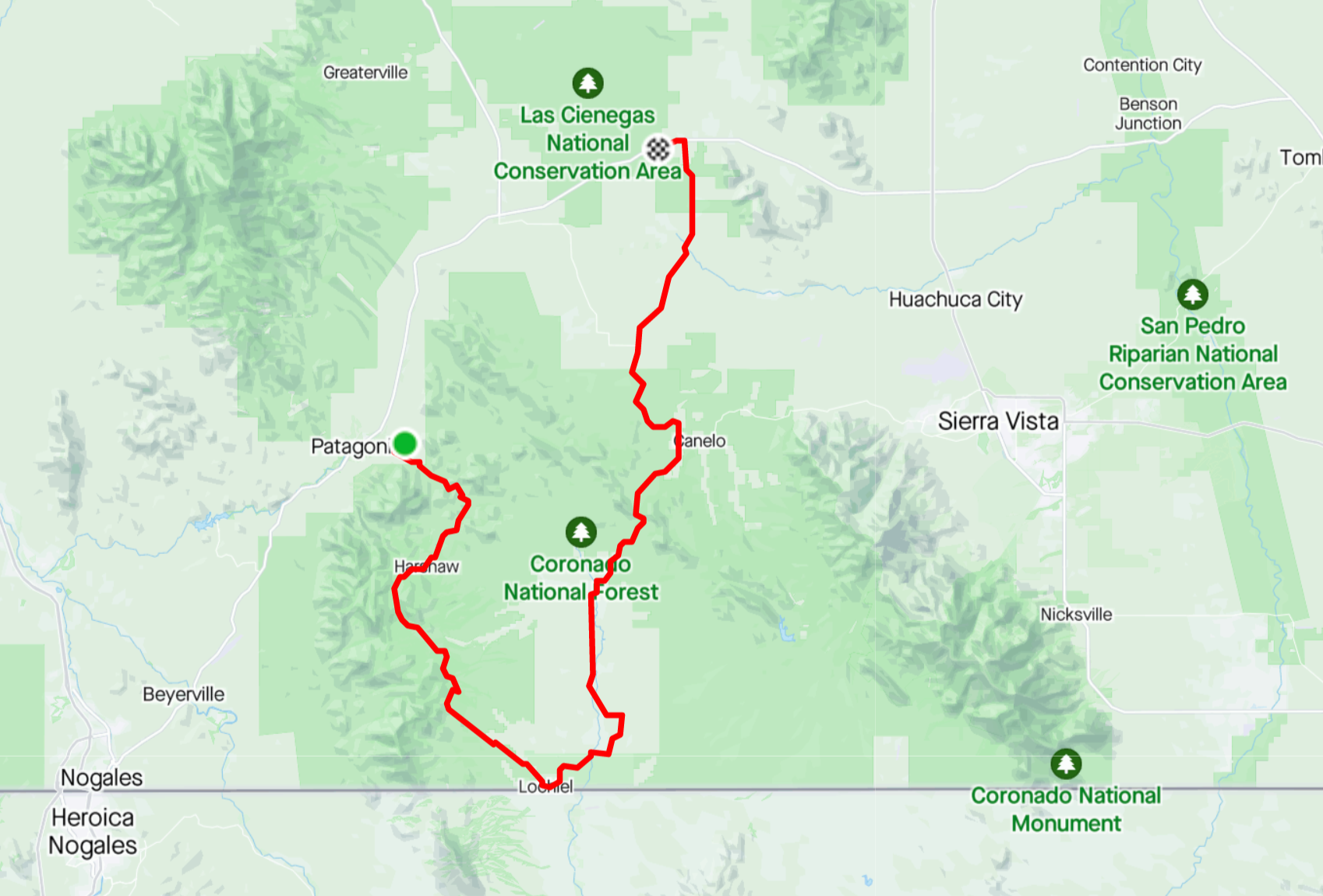

My route, that I'm showcasing here today, I’ve dubbed “mine country to wine country.”

There are very few places that I’ve experienced by bike where I’ve felt so insignificant, dwarfed by the expanse of the landscape, in awe of its stark beauty, and grounded by the sounds and the silence that surrounds you like I have over the years here in the borderlands region of Southern Arizona.

My route takes you from the old Patagonia train station out of town on Harshaw Road, a bit of pavement that undulates its way south of town for about eight miles before turning to dirt by the old Harshaw townsite. All that remains of the town are a few houses, some building foundations, two small cemeteries and dilapidated mine shafts. Most of the buildings were torn down by locals or by the Forest Service in the mid to late 1970s. Ancient Fremont cottonwoods, Arizona’s largest trees, majestically burst out of the rocky creek bed that parallels the road, their weathered, hulking bodies like massive giants cheering for you as you pedal up the lower slopes of Red Mountain.

There’s been an ebb and a flow to the mining industry in this region and, currently, Patagonia is seeing a boom again due to the fact that silver and manganese, two sought after minerals, are being extracted by the South32 Mine, an Australian mining company who purchased the old Arizona Mining Inc. While they may have struck it rich with certain ore here, they also inherited the natural disaster that was left behind in the form of toxic tailings and a compromised water table —the one that also provides water for the town. The destruction of the hillside and trees for drilling pads can be clearly viewed from Harshaw Road and has sadly only gotten worse in the eight years that I have been coming here. The denuded slope is above Harshaw Creek and threatens to erode directly into the creek with the potential to smother downstream aquatic life with sediment.

All said and done my “mine country to wine country” route is 45 miles of gravel and 15 miles of tarmac, with just under 4K of vertical.

For the more intrepid, you could pedal the last 20 miles back to Patagonia on Highway 82, making it a clean 80 miles for the day, but I’m not sure why you’d want to do that if you didn’t have to.

Continuing up the mountain, the mine operations fade behind you and the terrain becomes more alpine and the air a bit thinner as you crest 5,000 ft. You pedal past the old mining town of Duquesne before beginning the drop into the San Rafael Valley and the old border crossing town of Lochiel, which is now basically deserted and consists of a few of the original buildings and some large cottonwoods.

The route is flat as you make your way onto the San Rafael Valley floor, a rare expanse of 90,000 acres of wide-open land, a mixture of both private and public lands, that sits 5,000 ft. above sea level. There’s a stillness and silence that centers the soul here, but this parched and quiet desert landscape simultaneously teems with vibrant life. Some 300 species of birds, 600 species of native bees, 300 types of butterflies and moths and over 100 threatened species of other types call the San Rafael Valley home. Ever heard of a coatimundi? I hadn’t either until we saw a band of twenty or so dart across Harshaw Road (imagine a really slender racoon with a long snout). While rare and elusive, there have been sightings of jaguars, mountain lions, and ocelots that migrate these mountains every season. Cattle ranching, very much still a part of this community, has been the predominant activity in this region for the past 175 years, and the pristine nature of this unique biome is due in large part to the stewardship of these dedicated ranchers.

Making your way east across this expanse, which could be straight out of a Spaghetti Western movie set (maybe that’s why I hear Ennio Morricone out here?), wheels pointed towards Canelo Pass, the last real climb of the day before descending into Arizona wine country. I know what you’re thinking: Wine country and Arizona don’t really seem to go together but you might be surprised to learn that there are six different appellations in the state, and that the Sonoita/Elgin wine country you're pedaling to has similarities to wine growing regions in Argentina.

You'll pass the oldest commercial vineyard and winery in Arizona, Sonoita Vineyards, which was started in 1974, and now includes over 30 acres of vines, and roll through the town of Elgin as you make your way across the valley with the Whetstone Mountains as a backdrop to the east.

There are various wineries to serve as your finish line, but I finished my ride at Rune Wines, Arizona's only off-grid solar-powered winery and tasting room, with 360-degree views of the surrounding mountain ranges and high desert grasslands, for a tasty glass of Syrah.

Cheers!

Thank you for reading 10 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Yuri Hauswald grew up on a farm in rural Petaluma, CA without a tv, which meant he spent plenty of time outdoors roaming the hills looking for adventure when he wasn’t doing his ranch chores. After a successful collegiate career playing lacrosse for UC Berkeley, and armed with a degree in American Literature, Yuri discovered the joys of mountain biking while teaching English at a prep school in Pennsylvania and hasn’t looked back since. A former two-time solo winner of the 24-Hours of Adrenaline and 9th place finisher at the 2006 24-Hour World Championships, Yuri has crisscrossed the country the past 20 years seeking out his next two-wheeled adventure. He turned pro at the tender age of 36 and in 2015, at the age of 45, won the 2015 Unbound 200.

-

-

“I haven’t found the ends of my ability yet”: a conversation with the forces behind gravel para-cycling

“I haven’t found the ends of my ability yet”: a conversation with the forces behind gravel para-cyclingPara cyclists Dr. Meg Fisher, Andrew Bernstein and Johanne Albrigtsen discuss inclusion, access and their love for the growing sport of gravel racing

By Emily Schaldach • Published

-

Remco Evenepoel obliterates Tenerife's Mount Teide Strava KOM

Remco Evenepoel obliterates Tenerife's Mount Teide Strava KOMReigning World Champion currently in altitude training before next week's Volta a Catalunya

By Tom Thewlis • Published

-

“I haven’t found the ends of my ability yet”: a conversation with the forces behind gravel para-cycling

“I haven’t found the ends of my ability yet”: a conversation with the forces behind gravel para-cyclingPara cyclists Dr. Meg Fisher, Andrew Bernstein and Johanne Albrigtsen discuss inclusion, access and their love for the growing sport of gravel racing

By Emily Schaldach • Published

-

Belgium to host inaugural European Gravel Championships this fall

Belgium to host inaugural European Gravel Championships this fallThe inaugural UEC Gravel European Championships, which will take place on October 1, 2023

By Anne-Marije Rook • Published

-

Bentonville Bike Fest introduces Gravelicious, a new gravel race in the mountain bike capital of the world

Bentonville Bike Fest introduces Gravelicious, a new gravel race in the mountain bike capital of the worldThe Bentonville Bike Fest presented by Mobil1 returns for a third year this May with a new venue, UCI competitions and new events.

By Anne-Marije Rook • Published

-

A Call of a Life Time: YouTube docuseries chronicling the Life Time Grand Prix premiers tonight

A Call of a Life Time: YouTube docuseries chronicling the Life Time Grand Prix premiers tonightThe six-part series promises a 'binge-worthy' behind-the-scenes look into the off-road cycling world

By Anne-Marije Rook • Published

-

'Freight Trains of Fun': Pace groups are now a thing in bike racing

'Freight Trains of Fun': Pace groups are now a thing in bike racingToday, gravel racing is becoming even closer to a marathon running experience with the introduction of pace groups at the upcoming Gorge Gravel Grinder race in Dufur, Oregon on April 23.

By Anne-Marije Rook • Published

-

Life Time Grand Prix unveils its 'wild card' event, the Rad Dirt Fest

Life Time Grand Prix unveils its 'wild card' event, the Rad Dirt FestHeld in Trinidad, Colorado in September, the Rad Dirt Fest will challenge the 70 series contestants with a 110-mile "Stubborn Delores" course.

By Anne-Marije Rook • Published

-

When life gives you lemons, you sell them: Meet the Floridian farmer who rode 80 miles a day to sell his produce

When life gives you lemons, you sell them: Meet the Floridian farmer who rode 80 miles a day to sell his produceMeet the Floridian farmer turned gravel racer who rode 80 miles a day on a 500-pound trailer-attached bike to sell his produce.

By Kristin Jenny • Published

-

UK to host first elite gravel race in May 2023

UK to host first elite gravel race in May 2023The Gralloch will be part of the UCI Gravel World Series, the sport's highest tier of racing

By Tom Davidson • Published