Hitting peak form is easier with the help of training apps - here’s how

We take a detailed look at the performance metrics available to amateur cyclists and help you establish how to use training software to get faster

- (opens in new tab)

- (opens in new tab)

- (opens in new tab)

- Sign up to our newsletter Newsletter

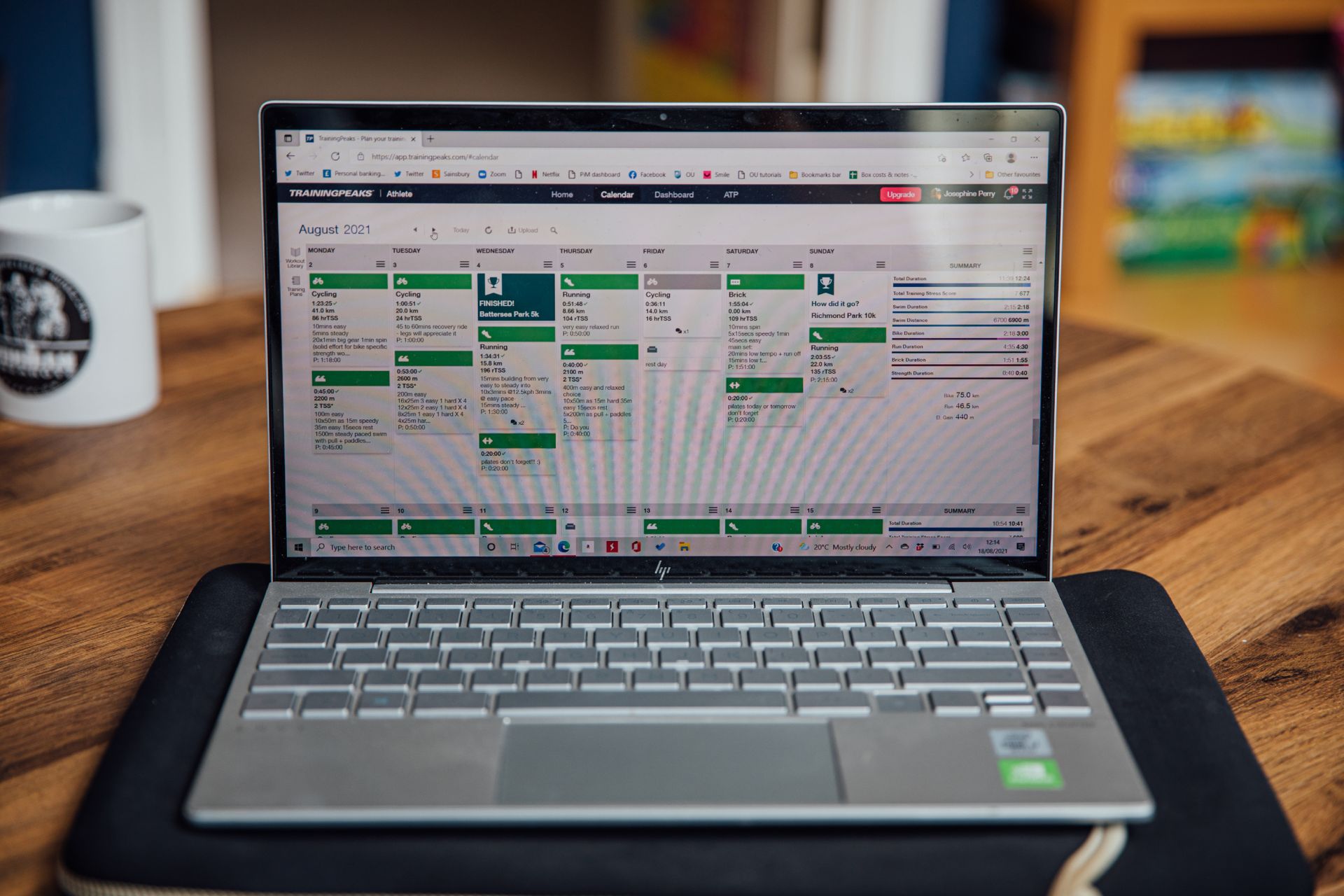

If you’re training in earnest for an event, or you’ve got an entire season of racing planned, then it’s highly likely that you’re using a form of training software.

It's entirely at the user's discretion how deep they delve into the tools available to them. Athletes can simply manually log the number of hours and minutes spent riding a bike, or they can use the software as a daily log of absolutely every element of their physiology and psychology.

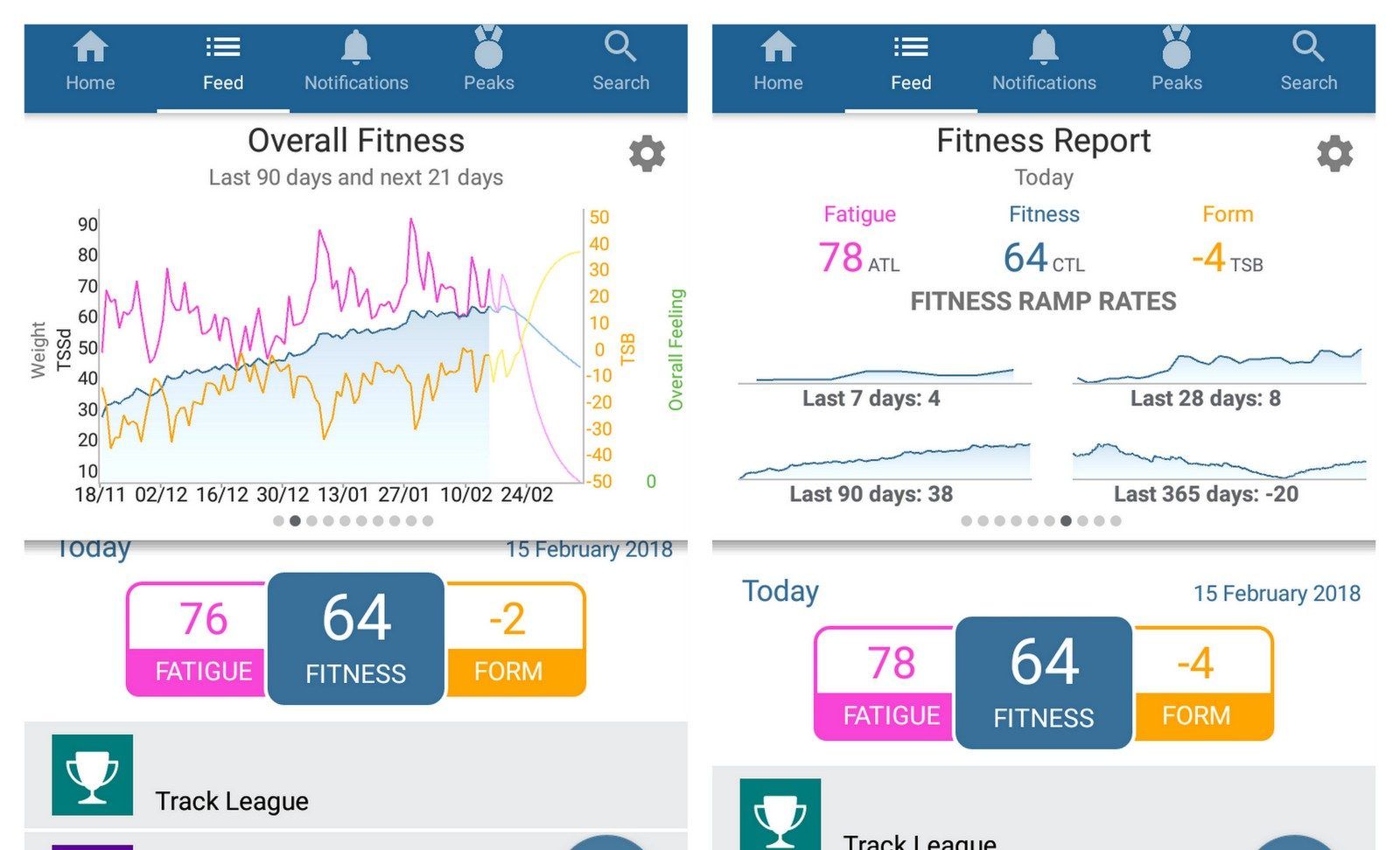

Those looking to use the software to train their bodies to be ready for a specific event, on a specific date, will likely have further explored the capabilities of their chosen software, using charts that track metrics like fitness, fatigue and form.

What are Performance Management Charts?

Most training software options offer a pictorial view of an athlete’s fitness based on their training load, fatigue level – and resulting freshness.

Popular training software options on the market are Training Peaks (and its more advanced sibling WK04), Today’s Plan, Golden Cheetah and to a lesser degree Strava.

They each employ their own terms and algorithms. In the interests of making a fairly complicated topic a little easier to explain, we’ve stuck with the terms used – and in some cases trademarked – by Training Peaks.

Glossary of Training Peaks terms:

- Performance Management Charts – the pictorial view which charts the metrics below

- TSS – Training Stress Score – Training Impulse of a given session

- IF – Intensity Factor – how hard a session pushed your body based on watts produced/heart rate, and your current fitness

- CTL – Chronic Training Load – Fitness - training load from last 42 days

- ATL – Acute Training Load – Fatigue - training load from last 7 days

- TSB – Training Stress Balance – Form – how you should be feeling and performing based on CTL and TSB

How do Performance Management Charts work?

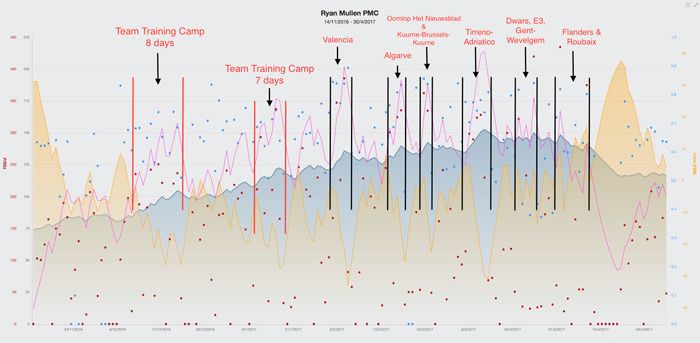

Credit: Stephen Gallagher

The chart above shows Cannondale-Drapac Rider Ryan Mullen’s Classics Campaign, as analysed by Stephen Gallagher of Dig Deep Coaching (opens in new tab) – there's a detailed review on written by Gallager himself on the Training Peaks site. (opens in new tab)

Discussing the system, five-time British cyclo-cross champion and Dig Deep Cycling (opens in new tab) coach Ian Field told us: “Ultimately we can use all these numbers to predict performance on a given day. There are possible downfalls, but I’ve used it for four to five years for myself, and I've found it to be fairly accurate.

"When I first started using it, I really wanted it to fail – I'm really more a hands-on person, not massively into numbers – but nine times out of ten I’ve found when you’ve worked out what works for you – and it is very individual – you can predict performance for your goal events.”

The entire system is based on your TSS following each given session. TSS is a term that belongs to Training Peaks, but you'll find a very similar principle used elsewhere (Suffer Score, if you’re living in an orange world with segments to hunt for, for example).

“TSS is a training impulse. It's based off FTP [Functional Threshold Power] and makes evaluating one session quite easy. It's relative to intensity and duration – it takes into account how hard you've gone and for how long.”

Riding at FTP for one hour would give you a score of 100 – that's the maximum you can score (since you shouldn't be able to do more than your one-hour power for an hour). Field suggests intervals sessions will be about 50 or 60 for an hour.

Once you know what sort of TSS your go-to sessions typically yield, you can plan entire training weeks with the optimum TSS, tailored to your targets. Which is where incorporating CTL and ATL to peak for an event comes in.

“TSS can be presented on a chart – this has three lines – CTL [Chronic Training Load], a 42-day rolling average. This is your fitness. ATL is Acute Training Load – that's what you've done in the past seven days – and is called fatigue. The final line is TSB – Training Stress Balance. This is often called form – how well you're going on a specific day.

“So in an ideal world, before an event, you see your CTL gradually rise [leading up to the event], you then back off during a taper period and ATL will drop [in the week or so prior]. That means that your form [TSB] should rise – the result should be that you're going well.”

Field says that the recommended number to “feel really good” is between five and 15, though he’s keen to point out that as per all of this it’s very individual. The best form will always be on an upward curve – letting your TSB drop to the right number is nowhere near the same experience as letting it rise from a point where you were in the negatives.

With this knowledge you can manipulate your training and taper weeks – adding in the values, checking the chart – and changing them until you hit the sweet spot.

What are the limitations?

There are, however, some limitations to bear in mind.

The very basis of all of this – TSS – isn't infallible. As Field says, problems occur "when a watt is not a watt" – for example when it’s hot, your body will suffer more for the same results. If you’re using heart rate to calculate all of these metrics, you’ve got to understand that heat, fatigue and things like caffeine dramatically affect it.

Ex-pro and director at Dig Deep Coaching (opens in new tab), Stephen Gallagher, has used these metrics extensively – but he says amateurs using them to plan their own training need to be well aware of the pitfalls.

“The performance management charts and the detail within each ride is dependent on the accuracy of your cycling training zones. If you have your zones wrong – for example your FTP changes and you don’t update it – the trace that you're following, whatever you're tracking in terms of ATL, CTL, is inaccurate. That's a big area people don’t realise,” Gallagher says.

“The other thing is that a lot of the zones are set on FTP – that's the traditional approach. But FTP doesn’t dictate intensity of every ride. Some people can have a lot more fatigue from doing V02 efforts than threshold. It doesn’t take into account individual physiology – you may be dominant in another area, so if TSS is based off FTP it won't always be accurate – and that will throw your other data out. Threshold isn’t always representative of how hard a session is on an individual.”

Some activities are harder than TSS would suggest they are, too. Gym sessions where heart rate remains low for the relative amount of muscle damage, for example, are hard to provide values for – and as Gallagher puts it: “I do a lot of mountain biking and the training stress I get from that isn’t reflective of my broken body as I come in the door after a two-hour mountain bike ride.”

All this information needs to be used and applied with knowledge, too.

“A misconception people have is that CTL needs to be higher and the higher it is, the better your fitness is. That’s not necessarily correct – it tells you how much load you've done for that period. We have a lot of people who come to us and want to get CTL as high as possible: you can get that by just riding your bike four hours a day, but it won't necessarily make you faster. It can be used to help ramp your training but it has to be used in relation to intensity of sessions.

"How you approach your training, and how much of a ramp your CTL is, can be dictated by your event. Take a track rider: it's not possible to get a large spike as a lot of your rides will be 60-90 minutes and intense, while someone training for a gran fondo will ramp their CTL up quite a bit."

The two riders will need to reach whatever their ideal CTL is via different routes, too. A high CTL could be achieved via logging many four-hour rides, but with low intensity factored in, that athlete would probably get dropped like a stone from the start line of a crit race.

Considering individual factors is crucial. “You also need to be aware of what CTL you can handle. Someone who works 40-hour week, has a family and other commitments can't raise their CTL as high as someone with the same FTP and more time to recover. External factors can have just as much effect on performance as training sessions and weekly training stress."

WKO4 – the advanced tool from Training Peaks – allows you to track more of this, but it can't take into account every factor such as the all-night wail of a newborn baby.

How should we using training software?

On the whole, Gallagher doesn't advocate all amateurs poring over the numbers for hours on end.

“It's a gauge. Individual sensations are as important as what it says on the software. We have some people who focus a lot on these charts and it’s not healthy in a lot of cases. Technology has unfortunately dulled our senses and stopped us using our own common sense and what we feel in ourselves about what we should be doing and training.

"You can’t let lines on a chart dictate how you think you’re going – it doesn’t tell you exactly how you’re feeling. You need to be able to listen to yourself,” he says.

This is not to say that amateurs shouldn’t be using training software – more that we don’t need to get bogged down in all the wrong numbers.

Gallagher says: “The principle [of a training diary] is to tell your story. Whatever you use, the more information you have the better enabled you are to tell your story in the future."

“From a coaching point to view, when somebody comes on for coaching and they have a lot of data and information from their past, it's so much easier to get a snapshot of that person. We can look at it and see what worked and what didn’t. You can have a coach do that, or you can do it as an individual, but you need that background of information to work out what worked and what didn’t.”

He adds: “The ability to plan your training and focus going into an event is now so much easier. We live in an age where everything is on your phone – your calendar, work meetings – and it's exactly the same with training software: you can be very specific and you can organise yourself based on how much time you have and being able to use that going forward. Regardless of power, heart rate zones, that's the essence of most of the software people use.”

While Performance Management Charts are created specifically to help athletes peak for events, Gallagher reckons combining personal knowledge and information along with tracking fitness via software brings the best chances to peak perfectly. With a well used, detailed training diary, you can do it based on just looking at what you’ve done in the past.

“One of the benefits [of keeping a proper training diary] is being able to look at templates of what you've done before. Having the data along with the personal knowledge on how you felt and the sensations at the time is a great way to understand what worked and what didn’t.”

What does a 'perfect' taper look like?

If you want to peak for a target event, a taper – period of preparation – is going to feature. It's during the taper that you'd expect to see ATL (fatigue) drop and TSB (form) rise.

The perfect taper varies dramatically between individuals but the general principle is to lower volume but maintain some intensity.

“In my opinion, and with quite a big scientific backup – the best taper is approximately 10 days and a really good way of doing it is day on, day off,” says Field.

“Then you’re getting adequate recovery, but going really hard on the ‘on’ days. A good taper means cutting back the volume, but keeping the same number of sessions as a normal week – so riding your bike just as many times as normal, but bringing the volume down and keeping the intensity.”

The bottom line

Training tools and performance metrics can provide amateur cyclists with a huge wealth of information. However, it’s not the be all and end all – there’s nothing wrong with simply going on feel and listening to your body.

No matter what approach you take, keeping a detailed training diary will help you to look back at past events and establish what sort of approach helped you to be in your best (or worst) form – so you can avoid past mistakes and be an even better version of yourself the next time around.

Thank you for reading 10 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Michelle Arthurs-Brennan is a traditional journalist by trade, having begun her career working for a local newspaper, where highlights included interviewing a very irate Freddie Star (and an even more irate theatre owner), as well as 'the one about the stolen chickens'.

Previous to joining the Cycling Weekly team, Michelle was Editor at Total Women's Cycling. She joined CW as an 'SEO Analyst', but couldn't keep her nose out of journalism and in the spreadsheets, eventually taking on the role of Tech Editor before her latest appointment as Digital Editor.

Michelle is a road racer who also enjoys track riding and the occasional time trial, though dabbles in off-road riding too (either on a mountain bike, or a 'gravel bike'). She is passionate about supporting grassroots women's racing and founded the women's road race team 1904rt.

Michelle is on maternity leave from July 8 2022, until April 2023.

-

-

High-end bikes still in demand says Giant, as it announces 12.5% revenue increase

High-end bikes still in demand says Giant, as it announces 12.5% revenue increaseBut like much of the industry the Taiwanese manufacturer is also experiencing a surplus of low to mid priced stock

By James Shrubsall • Published

-

Milan-San Remo 2023: Route and start list

Milan-San Remo 2023: Route and start listAll you need to know about the first Monument of the 2023 season

By Ryan Dabbs • Published

-

How to get stuck into crit racing: everything you need to know before your first crit race

How to get stuck into crit racing: everything you need to know before your first crit raceOne of the fastest and most fun forms of bike racing, we've gathered advice from some of the best in the sport to help you succeed

By Colin Levitch • Published

-

Tapering for a big event: here's how to ace your lead-up to a important ride or race

Tapering for a big event: here's how to ace your lead-up to a important ride or raceWe talk you through how to best balance your training load for peak performance on race day

By Marc Abbott • Published

-

It's 'Get Ready for Racing Week' on Cycling Weekly: your guide to the prep you can do to achieve your racing goals

It's 'Get Ready for Racing Week' on Cycling Weekly: your guide to the prep you can do to achieve your racing goalsWith the racing season right around the corner (or already just begun for some), our week-long special runs you through how to get your legs and gear ready for race day

By Anna Marie Abram • Published

-

Follow our road racers' cycling training plan to sharpen your racing edge

Follow our road racers' cycling training plan to sharpen your racing edgeHere's how to get ready for a season of road racing - we've partnered up with Alzheimer's Research UK to bring you in-depth training plans for your cycling goals

By Anna Marie Abram • Last updated

-

The best energy gels for cycling 2023: what to look for and five favourites

The best energy gels for cycling 2023: what to look for and five favouritesThere's no doubting the benefit of downing a quick energy gel at vital points of a ride or race. Here's our guide on what to look for, as well as a few of our favourites

By Michelle Arthurs-Brennan • Last updated