How hormones affect cycling performance - and what you can do to harness them

No, testosterone won’t give you superpowers any more than being on your period writes off your race prospects. Michelle Arthurs-Brennan debunks the myths around sex hormones

- (opens in new tab)

- (opens in new tab)

- (opens in new tab)

- Sign up to our newsletter Newsletter

Sex hormones control so much more than our moods and desires. They play a critically important role in our athletic performance as well as in our general health. Understanding the fluctuations and possible deficiencies in the key sex hormones can help us be fitter, healthier – and yes, faster on our bikes too.

Each body has its own norms: our levels of hormones and sensitivity to them are individual. Hormone levels change at various stages of our lives, and can be disrupted by our own behaviour. Any disruption – whatever the cause – can have far-reaching implications for our cycling performance. I should know. My hormone levels were thrown into disarray first by hormonal contraceptives, and later by my failure to properly fuel my training.

What are sex hormones?

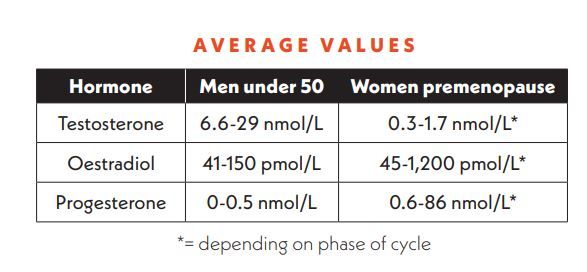

Without getting too tangled up in the biochemistry, sex hormones are steroids: androgens, oestrogens, and progestogens. The angrogen testosterone is the primary sex hormone in men, and it has a powerful effect on athletic performance, aiding muscle growth and recovery, as well as stimulating the production of red blood cells, which carry oxygen to muscles. “In men, testosterone peaks during puberty,” says sports endocrinologist Dr Nicky Keay. “Young men develop bigger muscles, thicker bones, higher haemoglobin levels – that's all testosterone. And the difference in performance between men and women, which is about 10% in cycling, is mostly the result of testosterone.”

Men produce relatively low levels of oestrogens (of which oestrodial is the most important) and low levels of progesterone. Oestrogen is important in bone health for both sexes, and it also serves a cardioprotective function, but in women it plays a more far-reaching role, impacting power output, reaction times, moods, and playing a crucial role in reproductive health.

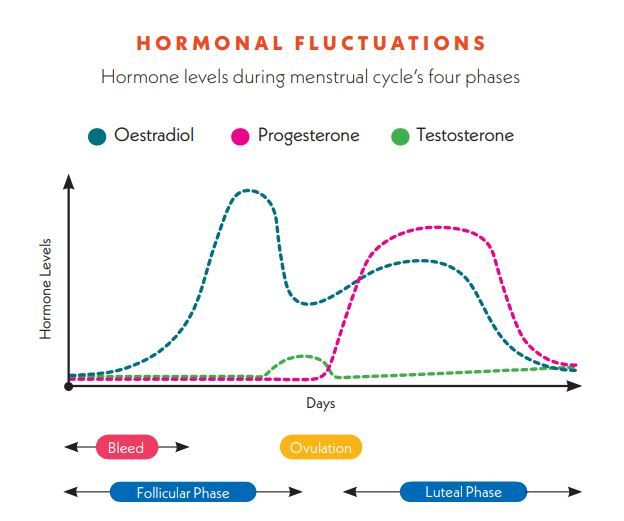

Peaking in the first half of the menstrual cycle, called the follicular phase, oestrogen helps the body make performance gains. Lead scientist at cycle tracking app Fitr Woman (opens in new tab), Dr Georgie Bruinvels, explains the effect of rising levels of oestrogen during this phase: “Your body's ability to develop muscle is increased, there’s an increased release of the feel-good brain chemicals dopamine and serotonin, oestrogen has neurocognitive benefits as well.”

Progesterone takes over in the second half of the cycle, called the luteal phase. “In response to progesterone, there’s a change in fluid dynamics, resulting in greater blood volume,” Bruinvels continues. “Progesterone increases body temperature, breathing rate, resting heart rate, it places more demand on your body, so your basal metabolic rate – the amount of energy you need – increases.”

It would be easy to leap to the conclusion ‘testosterone good’, ‘progesterone bad’, but our biology is far more complicated than that. Women and men have different hormone systems, with different receptors, and the processes being regulated are of course very different too. “A woman with higher than normal levels of testosterone isn’t automatically an amazing athlete,” says Dr Keay. “A woman with low levels of testosterone may still be very successful. Similarly, two women with the same level of progesterone may experience very different effects. It’s not an exact science.”

Keay is keen to defend the less popular hormone, which is essential to reproductive health, “yes, progesterone does have its downsides. But it is a counterbalance, if you leave oestrodial to its own devices, the endometrium gets too thick. You have to have it, if it’s too low, that can be a problem,” she confirms.

What about for men – does a high level of testosterone help them make gains? “Men tend to get hung up on testosterone and think more is better,” says Keay, “but elevating it [above natural levels] will exaggerate the effects – it will thicken the blood and cause health problems. It’s not a good idea, and not enough men realise that.” It’s important not to meddle with hormones, stresses the doctor, but rather keep the body healthy so that hormones are naturally regulated.

Are your hormones out of kilter?

‘Years of underfuelling left me hormone-deficient and broken’

Cycling Weekly tech writer Hannah Bussey raced her bike all over the world before a crash in 2009 brought her cycling career to an abrupt end. Only now, looking back, does she identify the signs of chronic underfuelling over many years

I’d always shrugged off crashes and broken bones as ‘just bike racing’, but a permanent plate in my right clavicle, and a double fracture of the pelvis saw me walking away from a sport I’d once loved.

It hadn’t dawned that perhaps my multiple fractures, now nudging double figures, lack of regular menstruation, spells of overwhelming exhaustion and confusion were all related. It was only after I had my daughter, unsuccessful multiple treatments for stress incontinence and a fractured foot from running that my consultant started joining a series of red flags together.

A series of blood tests revealed that all my hormone levels were so low they barely registered. I was fortunate to have an incredible specialist in premature ovarian insufficiency in my corner, who pulled together a team of specialists, including regular DEXA scans, which revealed osteopenia. They got me on the right doses of HRT and testosterone treatment in order to prevent further problems.

It’s been a long haul, but I finally feel the brain fog lifting. I’ve had to prioritise weights in the gym over just time on the bike, which, along with a daily dose of testosterone, is helping to reduce the chance of developing full blown osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease.

Frustratingly though testosterone, isn't even licensed for use for women on the NHS, so I pay £80 every three months for a private prescription, just to get my levels back to what is considered normal for women to function. For our male counterparts who suffer with testosterone depletion it’s NHS funded, which demonstrates how far lagging in equality access to health still is.

Knocking your personal equilibrium out of balance is surprisingly easy. I went through years of missed periods before realising it was a sign of under-fuelling and sub-optimal health – and I’m far from alone. A CW survey in 2020 found that 30% of female and 15% of male respondents were at risk of harming their health by underfuelling, and the risk was significantly higher among semi-pro riders. Nearly 40% of women cyclists reported some level of menstrual dysfunction, and that’s having removed respondents on hormonal contraceptives.

The most common cause of sex hormone suppression, in women and men, is the failure to keep fuelling in line with energy demands, referred to by clinicians as relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S). This doesn’t only disrupt menstruation, it can seriously harm bone health too. How to prevent RED-S? Firstly, don’t presume you’re not underfuelling just because you’re not skinny. The body prioritises movement, and if not enough energy is available – for example, for a training session – it cuts back on other (vital) systems, gradually leading to problems.

Missed periods are the clearest tell-tale sign of RED-S in women. In men, reduced testosterone may be indicated by loss of libido, low energy and poor sleep. If you believe you are at risk, firstly seek medical advice – your GP can order blood tests. Addressing the cause is “multifactorial”, advises Bruinvels. “Obviously, nutrition is a fundamental part of that. Look at how often you're fuelling and whether your diet contains enough of all the macronutrients. If you’re riding fasted – which I am really, really against – be that riding pre-breakfast or postponing meals, it raises the risk, as does psychological stress, a big ramp up in training volume, or not getting enough sleep.”

The effect of hormonal contraceptives

The contraceptive pill is the most commonly used form of birth control among women in the UK, “it contains synthetic oestrogen and progesterone, which fools the brain into thinking levels are high, so it stops sending messages to the ovaries,” explains Keay. “The rest of the body is not fooled. That’s why [the synthetic hormone] is not bone-protective in athletes with RED-S, for example.” In other words, artificial hormones do not compensate for any natural shortfalls.

Should female athletes avoid this form of contraceptive? “It's every woman's choice what she uses for contraception,” says Keay, choosing her words carefully, “but athletes have to be really aware and make an informed decision.”

There are cases where the pill is used to combat a medical condition. “If you have got polycystic ovary syndrome or endometriosis, then switching off all your hormones is actually really helpful. If you truly are having a dreadful time [in the second half of the cycle], I can see the rationale,” adds Keay. “For women who have high testosterone and don’t like it because they get [more] hair, we give the pill to lower testosterone - do women realise that they’ll have lower testosterone if they’re on the pill?” Keay asks.

Studies on the effect of hormonal contraceptives on athletic performance are limited and conflicting. However, according to women’s health expert Dr Stacy Sims, oral contraceptives are associated with “decreased VO2max, a decreased ability to adapt to high-intensity interval training (HIIT workouts), as well as significantly elevated oxidative stress.”

Cycle tracking how to

Lizzie Deignan: ‘Bloated, foggy, fatigued… then Superwoman!’

Winner of the inaugural Paris-Roubaix Femmes Lizzie Deignan (Trek-Segafredo) has noticed changes in how her menstrual cycle affects her training since becoming a mother in 2018

I never really understood the idea of syncing my training with my menstrual cycle. Before I had my daughter, I never suffered with any kind of PMS [premenstrual syndrome] or other symptoms affecting my training. It was only after having my daughter that I began to notice my cycle affecting the way I was feeling during different parts of the month.

I began to see a trend in my feelings and sensations based on my cycle. After a few months of making the same comments in my TrainingPeaks, I started to use a menstrual tracking app. I feel bloated, foggy, fatigued from the moment I ovulate to the moment my period arrives. The week of my period and after I feel like Superwoman!

To cater for this, I tend to do most intensity and strength work in the first two weeks of my cycle. In the second two weeks, I accept that my numbers or sensations won't be at their best, but I do what I can. I also have more carbs during this phase, as I can tell my body needs it.

I would love to say that syncing my training has made a difference [to overall form], but it hasn't, it is just reassuring to understand why I feel powerless at some points in my cycle. It does really bother me if a race falls at a time that I’m not at my peak. [In 2021] I had so many races where I felt completely compromised by my menstrual cycle. I try my best to stay positive and motivated because it is still possible to perform.

When I stopped taking the contraceptive pill and realised that my periods weren’t going to return unless I took a look at my training and lifestyle, the fix turned out to be frustratingly simple: I just had to eat more carbohydrates before, during and after exercise. Looking back, I’d fallen foul of the “low-carb” and “clean eating” media messaging relentlessly directed at women. It's hard to say how fixing my fuelling influenced my racing performance, as lockdown limited competitive opportunities, but I did lose weight and my FTP rose higher than ever before.

Once I started ovulating normally again, it took a while for me to refamiliarise myself with the return of that monthly pendulum swing from “invincible” to “exhausted and irritable”. How can we women use this fascinating, constantly shifting cycle of hormones to maximise our gains? While there are clear patterns of physiological response to hormone fluctuations, every woman is different: you’ll need to track your body’s own signs and signals and train accordingly to suit you.

The fluctuations we experience revolve around ovulation. One of the best cycling apps for women is Fitr woman which breaks the cycle into four stages: menstruation (phase one), the end of your period to ovulation (phase two), ovulation to the drop in hormones (phase three), and the premenstrual period (phase four). In the event of pregnancy, progesterone and oestrogen remain elevated. “Day one of the cycle is often a bit of a challenge, but from day two onwards, people typically tend to feel really good,” explains Bruinvels.

If that pattern fits your experience, then the first half of your cycle is your ‘power phase’ – the time to go hunting for gains. Some women with heavy or painful periods may find that the initial challenging period lasts longer than a day, in which case the advice from Bruinvels is to “pull back a little bit” on training. If you experience a lot of pain (dysmenorrhea) or heavy bleeding (menorrhagia), see your GP, as it may be a sign of an underlying problem – and it may well be treatable. Some women report feeling ‘flat’ or lethargic when ovulation takes place and hormone levels drop suddenly in the middle of the cycle, while others feel no noticeable effects.

In the latter half of the cycle, progesterone rises and reaches a peak, meaning you may feel a dip in form. We absolutely do not need to write off 14 days of every cycle. “We’ve found that readiness is often reduced [in phase three], where progesterone is at its peak, but it’s offset by doing exercise. When you exercise, you feel good,” Bruinvels tells me. “After that, in the premenstrual window [phase four], where hormones decline, research has shown there’s more inflammation, so pushing hard isn't necessarily advisable.” For many women, it makes sense to prioritise recovery and technique during the premenstrual window. Nutrition is also key, apps such as Fitr Woman or Dr Stacy Sims’ book “Roar” (see end of article for further reading) provide excellent tips for fueling to avoid bloating, impaired recovery and the increased metabolic rate during this phase.

What if your race day falls within phases three or four? Again, be reassured: elite women riders have won races during every stage of their cycles, and you can trust race day enthusiasm to take over. Even so, understanding your body’s personal responses can help you to tailor your training, for example with an early taper and an updated fueling strategy taking into account your higher metabolic rate and increased body temperature.

In all of this, we have to remember that we’re all individuals. Some women notice no symptoms at all and train just as effectively right through the cycle. “We can’t ignore that the majority feel better when oestrogen is high,” says Bruinvels, “and the majority feel worse when they're premenstrual – our data shows that – but everyone is different. We never want to overstep the science, because it is a really individual effect.”

The effect of ageing

Ageing is a well documented performance inhibitor, and our hormones play a role in this. “Men’s testosterone levels fall slightly as they age,” says Keay, “from about nine to 29nmol/L for a man under 50 versus eight to 27nmol/L for a man over 50 – it’s a subtle decline.” Greater drops in testosterone can be caused by underfuelling, over-training or poor sleep. For men who suspect this may be the case for them, a simple blood test is advised.

Ageing affects women’s hormones in a more profound way. “For women, the ovaries stop producing oestradiol, testosterone, progesterone – the whole lot goes off a cliff,” says Keay. “[Menstruating] women, when we ovulate, the peak might get up to over 1000pmol/L [of oestrodial], whereas after menopause, we’re lucky if we get up to 100pmol/L. It’s a 10-fold decrease.” This has serious implications for athletes. “The consequences of this change for women is that they’re more likely to get injured, have weaker bones and, with less testosterone, slower recovery. Because oestradiol is cardioprotective, women’s incidence of cardiovascular disease goes up to equal to men after menopause."

It sounds bleak, but it really doesn’t have to be. “The NHS recommends lifestyle changes, which for female athletes means looking at your training, cycling nutrition and recovery,” says Keay. “Factor-in more recovery, more strength work, and really nail protein intake to keep muscle strong.” Aside from lifestyle changes, there’s hormone replacement therapy (HRT) to consider. “The British Menopause Society recommends it because it improves overall quality of life,” Keay explains. “If you feel dreadful and you can’t do what you want in life, don’t just put up with that. You’re not on the scrap heap just because you’ve reached menopause.” Finding your ideal HRT combination may require some trial and error. “The buzzword with HRT is personalisation. It's a case of finding the dose that's right for you,” Keay continues. “Don’t be conned by misleading marketing. The bottom line is, inform yourself, then go to your GP – and don’t be fobbed off with antidepressants.”

The term “individual physiology” and the plea “inform yourself” were emphasised again and again by the experts I spoke to for this feature. If you take away nothing else, make it this. Be you male, female, young or old, knowing and understanding your body is key. That may mean requesting blood tests, downloading an app, tracking your bodily sensations in a paper diary or in an Excel spreadsheet – whatever it takes to maintain that happy hormone harmony that your body strives for will prove worth the effort in the long term.

Resources

We covered a lot of ground in this article, if you'd like more information on any area, we wholeheartedly recommend:

- British Association Sport and Exercise Medicine endorsed courses for female athletes and coaches

- British Menopause society for advice on HRT

- Fitr Woman App by Orreco Health

- FourthEdge for athlete blood tests and female hormone mapping

- Sarah Hill, This Is Your Brain on Birth Control: The Surprising Science of Women, Hormones, and the Law of Unintended Consequences

- Dr Stacy Sims, ROAR: How to Match Your Food and Fitness to Your Unique Female Physiology for Optimum Performance, Great Health, and a Strong, Lean Body for Life

Thank you for reading 10 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Michelle Arthurs-Brennan is a traditional journalist by trade, having begun her career working for a local newspaper, where highlights included interviewing a very irate Freddie Star (and an even more irate theatre owner), as well as 'the one about the stolen chickens'.

Previous to joining the Cycling Weekly team, Michelle was Editor at Total Women's Cycling. She joined CW as an 'SEO Analyst', but couldn't keep her nose out of journalism and in the spreadsheets, eventually taking on the role of Tech Editor before her latest appointment as Digital Editor.

Michelle is a road racer who also enjoys track riding and the occasional time trial, though dabbles in off-road riding too (either on a mountain bike, or a 'gravel bike'). She is passionate about supporting grassroots women's racing and founded the women's road race team 1904rt.

Michelle is on maternity leave from July 8 2022, until April 2023.

-

-

Milan-San Remo 2023: Route and start list

Milan-San Remo 2023: Route and start listAll you need to know about the first Monument of the 2023 season

By Ryan Dabbs • Published

-

Summit finish and final day time-trial for 2024 Tour de France finale in Nice

Summit finish and final day time-trial for 2024 Tour de France finale in NiceStage 20 will finish atop the Col de la Couillole before final day race against the clock in Nice

By Tom Thewlis • Published

-

Female-specific nutrition strategies: how to adjust your fuelling at each stage of the menstrual cycle

Female-specific nutrition strategies: how to adjust your fuelling at each stage of the menstrual cycleYour carbohydrate and protein demands vary greatly throughout the month - here’s how to make sure you’re giving your body what it needs

By Andy Turner • Published

-

Strava data shows women restricted by daylight hours for exercise - but female Gen Z Brits prove more active than men

Strava data shows women restricted by daylight hours for exercise - but female Gen Z Brits prove more active than menGlobal data reveals women 8% less likely to exercise outside post-sunset

By Anna Marie Abram • Published

-

Seven ways ‘traditional’ cycle training approaches don't work for women - and what you can do instead

Seven ways ‘traditional’ cycle training approaches don't work for women - and what you can do insteadFemale physiology demands a different approach to training, nutrition, weight management and recovery – Dr Stacy Sims explains

By Deena Blacking • Published

-

It's 'Women's Week' on Cycling Weekly: your guide to the training, tech and inspirational tales of (and by!) cycling's key women

It's 'Women's Week' on Cycling Weekly: your guide to the training, tech and inspirational tales of (and by!) cycling's key womenWe've got detailed articles on training with the menstrual cycle, a look back at the woman who entered the 1924 edition of the Giro d'Italia, and a dive into 'women-specific geometery' and its relevancy today - plus much, much more!

By Anna Marie Abram • Published

-

Stock bike setups are often stacked against women and smaller adult cyclists - here’s how to achieve a better fit

Stock bike setups are often stacked against women and smaller adult cyclists - here’s how to achieve a better fitFrom frame size to stance width, crank length to brake levers, here's eight common issues faced by smaller adult cyclists – and a bike fitter’s advice on how to overcome them

By Nicole Oh • Last updated

-

Cycling and pregnancy: expert advice on staying active whilst growing a little person

Cycling and pregnancy: expert advice on staying active whilst growing a little personCycling Weekly's digital editor was never going to spend 40 weeks off the bike...

By Michelle Arthurs-Brennan • Last updated

-

Three's peak: How a trio of veteran women TT racers set a blistering new Three Peaks record

Three's peak: How a trio of veteran women TT racers set a blistering new Three Peaks recordThree women, three peaks, one target: to hike up and down each mountain, cycling from one to the next, in record time. CW finds out how they got on

By David Bradford • Last updated

-

Ideal time of day to exercise differs between active men and women

Ideal time of day to exercise differs between active men and womenDig deep and make it count - new research shows that the optimal time of day to burn fat is not the same across the genders

By Anna Marie Abram • Last updated